The Role of Baboon Rangers – Insights from My Master’s Thesis

(By Alice van Veen)

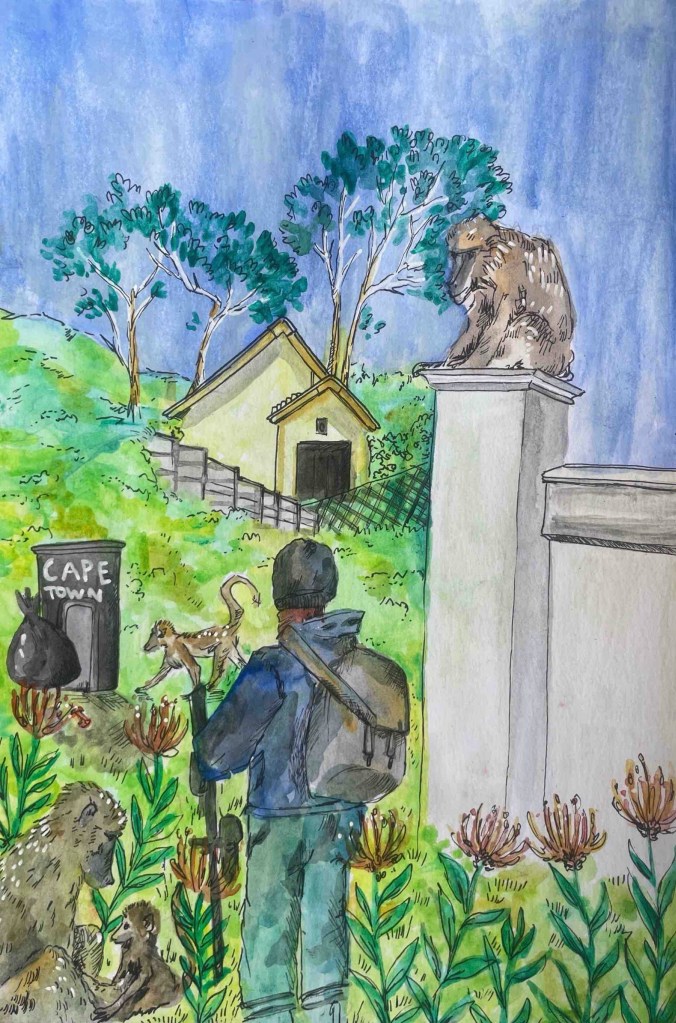

Baboon rangers are on the frontlines of managing daily interactions between humans and baboons on the Cape Peninsula. They are tasked with keeping baboons out of urban areas to minimize negative encounters. The Urban Baboon Programme is unique in its size and the way it manages wildlife. For my Master’s degree at the Stockholm Resilience Center, I had the opportunity to join the Unruly Natures project and gain insights from rangers. Their perspective has received little attention in the current discourse despite spending extensive time with baboons and playing a key role in on-the-ground wildlife management.

I began my fieldwork with several visits to observe rangers on the job and understand their daily tasks and working area. Following this, I conducted 13 interviews with experienced rangers from different troops. Because the rangers’ work is influenced by external factors like the landscape, the interviews were not traditional sit-down conversations. Instead, the rangers guided me through the areas where they work, allowing the surroundings to illustrate their stories and spark more meaningful conversations. The interviews lasted between two and four hours because rangers had so much to share and show!

What stood out during the interviews was how much of the rangers’ expertise is embodied and built in the field. While their training provided a basic foundation, rangers relied primarily on years of hands-on experience. For example, they can recognise individual baboons, interpret cues and anticipate troop movements. They also have an in-depth spatial understanding of both the natural and residential areas including likely entry points and common routes taken by the baboons. Equally striking was the personal involvement, as many rangers expressed care and affinity for the troops they manage and were concerned with their well-being.

Rangers also talked about the difficulties they faced on the job. One example that was raised by all rangers was how baboons can work out which properties are out of reach for the rangers, and use them to avoid being pushed out of urban spaces. Rangers’ ability to do their job also varies greatly depending on the area, where steep terrain and thick vegetation are difficult to move through, and the residents who live there, who can make the work easier by help rangers access areas they need to reach the baboons. How baboon presence should be managed is a contested subject on the peninsula, and rangers regularly meet a wide range of opinions. Annoyance with baboon behaviour, fear or frustration over damage caused by baboons sometimes results in residents expressing themselves disrespectfully towards rangers. Balancing these social, physical, and environmental conditions is a challenging part of their work. Despite this, rangers emphasized the many instances where residents made their work easier through baboon-proofing, proper waste management, and helping rangers move through neighbourhoods more easily.

The fieldwork took place during a turbulent time for the Urban Baboon Programme, in late 2024. The baboon rangers were working during the final months of the NCC contract and the future of their employment was uncertain. This study highlighted how rangers’ knowledge largely comes from years of working closely with specific troops. It is important to recognize and preserve this expertise for the well-being of both baboons and the people living in areas visited by baboons.

I would like to thank all the baboon rangers and NCC for making this fieldwork possible and to Johan and Kinga for their support. If this post has sparked your interest you can find the full thesis here. The results section might be especially interesting to read (pages 15 – 27).

New article, and an upcoming conference!

(By Johan Enqvist)

We are incredibly grateful for Alice’s important contribution to this project, the rangers are a key group whose voices are rarely heard in the baboon debate.

On our Outputs page you will also find a new research article, which has just been published in the academic journal Earth Stewardship. Titled “Mobilizing stewardship through theater: Pathways to transform polarizing conservation conflicts,” it is an analysis of the data we collected during the first tour of Unruly in June 2024. Using the arts in academic research is becoming more common, and in this article we analyse the different ways in which it can impact audiences and help stimulate change in a polarised, difficult issue. We identify four key mechanisms: embodying different lived experiences with baboons, imagining new ways of interacting with nature, learning from other people’s perspectives, and caring for human’s and non-human’s situations.

The full article is available for free here, and both it and Alice’s thesis have been added to our Outputs page. We have three more manuscripts that will be submitted for publications in the next few months, so stay tuned for more reading!

Last but not least, Kinga and I will attend a scientific conference organised by the Transformations Community, Earth System Governance Project, and Wits University next week in Johannesburg, as will the Empatheatre team. The Unruly play will be performed live at the conference, and we will present findings from our work to an international audience, and have it scrutinised by other scholars. This is an important part of making the research relevant beyond South Africa, and give us a chance to also learn from others doing similar work.